Know Your Adversary

What is human-centered, mission-driven digital security?

This is an excerpt from my newsletter, which you can totally subscribe to. It is also a very simplified way of thinking about the digital aspect of what is called holistic security.

To me, practicing digital security is about protecting people and not things. Living, breathing human beings are infinitely more valuable than whatever data (e.g. money) is stored on a piece of machinery. That’s why I draw a line between working with activists and journalists, and e.g. corporations or the authorities.

All organizations need security but there is a difference in kind between helping protect ‘assets’ and helping protect human beings. Assets do not protect themselves, but people can be empowered to take better care of their safety.

For this to happen, a threat model is the most important security tool. It is not a technical tool, but an ideation tool for thinking critically about security. It is a cycle that consists of several steps of analysis. Once you have completed the cycle, you can perform it once again, deepening the analysis and appropriate security implementations. How deep you go is a question of resources (such as time!)

Speaking of resources, security has costs, especially in efficiency. It takes longer time and more effort to have better digital security practices, but it is a good idea to treat these costs as an investment, where you hedge against the risks that you mitigate.

You can see it like this: The costs of practicing better security now is less compared to the cost once you have an unprepared-for security incident. Security practices don’t prevent security incidents entirely, but if implemented well, they make them less costly.

On top of that, a robust security culture also enables entirely new opportunities. It can be seen as a foundation that allows new things to happen and more things to happen because of the risk it mitigates. It is possible to speak more freely over an encrypted channel than a clear one, making better information sharing and decision-making possible (ideally speaking, you know, this is human beings we are talking about here).

This is of course a rather simplified and basic outline of what actual threat modeling should be, but hopefully enough to convey the idea that security is a process rather than a product. It’s fruitful to do the following exercises in a group of trusted peers.

Your Mission (if you chose to accept it)

First of all, being mission-oriented means that your security practices should be thought of as a way of doing what you intend to do, but doing it better. Digital security should not become a barrier to doing the work you intend to do. It should take as its point of departure the perspective of your ‘mission’.

Exercise: Try to formulate your mission in a few short sentences. What are you doing and why are you doing it?

This can be phrased as a one-liner (e.g. my mission here is to help people be safer online), or it can be elaborated into a longer mission statement (e.g. I would describe at length how, by helping people better take care of themselves online, I want to increase the degree of freedom and social justice in the world. Or something).

It is important to keep in mind that what one wants to do and what one actually does is not necessarily the same thing. That is why this first step is important. It’s about analyzing your motives, goals and strategies.

The Threat Environment

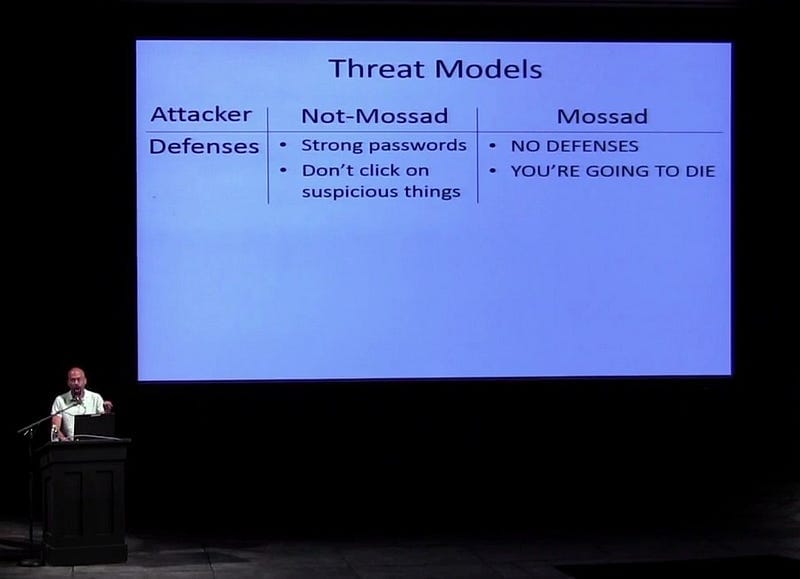

What kinds of adversaries do you have? According to security researcher Mikko Hypponen, you can group potential digital attackers into three rough categories: criminals, states, and, for lack of a better word, ‘hacktivists’.

We have online criminals. […] And the motives of online criminals are very easy to understand. These guys make money. They use online attacks to make lots of money, and lots and lots of it. We actually have several cases of millionaires online, multimillionaires, who made money with their attacks. […] These guys make their fortunes online, but they make it through the illegal means of using things like banking trojans to steal money from our bank accounts while we do online banking, or with keyloggers to collect our credit card information while we are doing online shopping from an infected computer.

Criminals are for the most part ‘unintentional adversaries’. A popular analogy is comparing them to a bear in the woods. When you and your friends are attacked, in order to outrun the bear, you don’t have to run the fastest as long as you are not running the slowest.

Or, as Bruce Schneier puts it,

A conventional hacker or criminal isn’t interested in any particular target. He wants a thousand credit card numbers for fraud, or to break into an account and turn it into a zombie, or whatever. Security against this sort of attacker is relative; as long as you’re more secure than almost everyone else, the attackers will go after other people, not you.

(An inportant exception to this rule is the example of an angry ex-partner that breaks into your accounts to disrupt divorce proceedings or for psychological harassment.)

Criminals are the main digital threat most people have to worry about. Whether doing political activism or not, you still want to keep your bank account and private life free from interference by this background noise of ambient threat.

The second type of threat are nation states. Here it is government agencies or so-called ‘state-sponsored actors’ doing the attacks. Often they are called APTs (Advanced Persistent Threats), a buzzword that Schneier thinks is justified:

An APT is different; it’s an attacker who — for whatever reason — wants to attack you. […] APT attackers are more highly motivated. They’re likely to be better skilled, better funded, and more patient. They’re likely to try several different avenues of attack. And they’re much more likely to succeed.

Against an attacker with state-backed resources, your are no longer trying to outrun your peers to get away from the bear. You are trying to outrun the bear itself. And in the words of security researchers the grugq and Ben Nagy, when it comes to security forces,

1. None of you can outrun the bear. Bears run at 60kph

2. The first person that gets caught by the bear won’t get eaten. They will snitch.

3. Next, the bear runs you all down, one by one, at 60kph, and kills you

4. The snitch will never do jail time, get a million dollars for their life story, and party at VICE.

Against state-sponsored actors, security is no a longer relative but absolute, and most likely absolutely broken. It is better to assume that you are always already compromised, and act accordingly, not with paranoia, but with extreme caution.

The last type of attacker is not motivated by money, and doesn’t have infinite resources at their availability.

»They’re motivated by something else — motivated by protests, motivated by an opinion, motivated by the laughs,« says Hypponen.

Sometimes called ‘hacktivists’, sometimes ‘trolls’, sometimes ‘the internet of garbage’, this is the type of attacker you might face if you are a woman online (yes, wtaf!?) or vocal on gender or LGBTQIA+ issues. An often used tactic of this type of threat is ‘doxxing’, i.e. the publication of private information without consent for the purpose of harassment.

Exercise: Besides the ambient threat of online criminality, which actors oppose your stated mission?

One way of mapping out your threats is to draw a two-dimensional graph with sympathy-antipathy on one axis and available resources on the others, and placing threat actors, perceived or documented, appropriately (also, allied actors, if you have time). This way you get an overview of the treat environment, which will help you make better security decisions.

One last threat…

Sometimes the closest adversaries are not criminals, states or harassers. Other threats to look out for are stupidity, error and accident, whether human or technical.

Critical Information

What information is critical for you to safeguard against the adversaries you have mapped out? There are two steps to approach this. The first step is to create a map of all the information you need to keep safe in order to operate in pursuit of your mission. You can either make a simple list or draw a conceptual map of how the different pieces of information are connected.

Often the connections, aka. metadata, are more important than the content. As an example, decision-making structures in organizations can be disrupted without ever having access to the content of the decisions.

When you have an information overview, you identify what information your adversary is most interested in, in order to disrupt what you are doing.

Remember that that the critical information map is in itself highly critical information. Have a shredder handy if you do this on paper.

Exercise: Create an information map for your mission. What information do you have, where is it kept, how is it communicated, who has access?

Vulnerabilities

You never attack where defenses are the strongest. This tactical wisdom is probably as old as war itself. When it comes to digital security, it is the same. An adversary will not attempt to break through where you have the best security, but will look for the weakest point. Unfortunately, this is usually us, the human beings behind the machines.

Most digital attacks today apply some form of social engineering. This means bypassing digital and physical barriers to exploit psychological vulnerabilities such as politeness (e.g. holding the door for a stranger entering a restricted building), curiosity (e.g. plugging the usb-stick you found in the parking lot into your computer), or trust (e.g. opening attachments in official-looking but emails).

The examples of different social engineering attacks are too numerous to mention here, but phishing-attacks, that is using email or other messages as a vector for exploitation, is by far the most prevalent method used today, regardless of which type of adversary you are facing.

Exercise: Put yourself in the position of your adversary and look at your security posture from the outside. Where are your defenses strongest? What are your weak points? If you were your adversary, how would you attempt to get access? By electronic means? Through physical access? Or psychologically?

Risk Assessment

Having mapped out the threats you face, the critical information pertinent to those threats, and your vulnerabilities, it is now time to do a risk assessment.

This is first of all an act of storytelling. Outline a set of very short stories of an attack where an adversary gets access to a piece of critical information by way of a vulnerability you have identified. This is not something you can do exhaustively, but try and produce enough outlines, so that you have a range of different incidents covered.

Once you have a set of security incidents outlined, it is time to assign each a risk value. This can be thought of as a two dimensional graph with likelihood or probability on one axis and severity or impact on the other. In short. what are the odds that a given attack will take place, and how much will it disrupt you from achieving your mission?

For each possible incident you have outlined, categorize the impact it will have on your operation (low, medium, high) and the probability of it taking place (low, medium, high).

Exercise: Considering your adversaries and vulnerabilities, what are the risks of an attack? Prioritize the risks with high probability, high impact first and descending.

Mitigation

Digital security consists of all the practices and tools you can use to mitigate digital risks. Since risks are highly dependent on the concrete adversary you face, there is not a simple way of completing the last exercise and often, especially if you are facing advanced adversaries it is important to get specialized practical and technical assistance in devising countermeasures. But generally the exercise would be this:

Exercise: In the order you have prioritized, go through the risks and assign an appropriate countermeasure (I know, right?)

I have already written about better passwords and touched briefly on compartmentation. These practices plus vigilance against attempts at social engineering are appropriate tactics in the face of a wide range of threats from unintentional adversaries. It is not possible to completely eliminate risk, but by these simple means it is possible to bring the most likely ones down to acceptable levels.

All the countermeasures taken together is your security plan. Of course this is not a static thing. The whole threat model is a cycle that has to be repeated regularly, as the threat environment evolves and as your mission gains new objectives.

Geopolitics…

There’s actually a step before the mission statement, and that consists of a geopolitical analysis: Who is doing what to whom in the arena that you are intervening in, and how will your intervention affect these power relations? This is something that should happen continually both on the ground and from a strategic organizational perspective.

Your mission should be formulated and reformulated as a response to this geopolitical analysis as it can change drastically, e.g. with the outcome of an election or coup or the outbreak of war or other types of conflict. This affects your mission and thus the threat environment. Depending on where you are in the world, I would suggest you review your threat model every one to three months or so, plus whenever the political plate tectonics start to shift beneath your feet.

Originally published at tinyletter.com/asymmetries/.